Breaking News: Over 800 Lives Lost in MinutesUnveiling the Terrifying Truth Behind the SS Eastland Disaster, Darker than the Titanic and Forgotten for a Century!

On a rainy summer morning in July 1915, the Chicago River became the site of a tragedy that would claim more lives than the Titanic or the Lusitania, yet its story remains cloaked in obscurity. The Eastland, a passenger steamship intended for excursions across the Great Lakes, was meant to ferry workers from Western Electric, along with their families, on a festive trip across Lake Michigan. Instead, it transformed into the scene of the deadliest shipwreck in the history of the Great Lakes, a catastrophe that unfolded in mere minutes, leaving behind a haunting toll of 844 souls lost at the heart of Chicago.

What was supposed to be a jubilant morning quickly turned fatal. At 7:18 AM on July 24, 1915, E.W. Sladkey, an employee of Western Electric, made a desperate leap from the dock to board the Eastland as its boarding gangplank was hoisted upward. This 84-meter majestic steamer, docked along the banks of the Chicago River, was brimming with 2,573 eager passengers and crew, all buzzing with anticipation of the day’s festivities. The ship, one of five charters reserved to carry workers from the Hawthorne Works of Western Electric in Cicero to a company picnic nearly 61 kilometers away in Michigan City, Indiana, was set to be the highlight of their social calendar. For many, it was a rare Saturday offan opportunity to dance, socialize, and temporarily escape the grind of manufacturing telephone equipment.

Among the crowd were George Sindelar, a foreman, accompanied by his wife and their five children, as well as James Novotny, a carpenter, who was there with his wife and their two little ones. Young women like 22-year-old Anna Quinn and 16-year-old Caroline Homolka dressed in their finest clothes, hoping to catch the eye of eligible bachelors. As a band played merrily in the main cabin and passengers vied for seats on the upper decks, a constant drizzle led many women and children to seek refuge below deck.

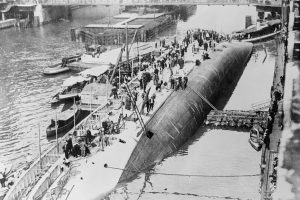

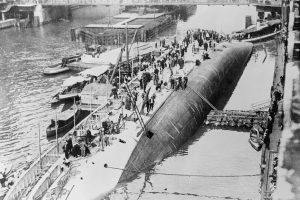

By 7:10 AM, the Eastland was filling quickly, with federal inspectors clocking in 50 passengers boarding per minute. With a permit to carry over 2,500 people, the ship was nearing full capacity. However, as it took on more passengers, it began to tilt to port, drifting away from the dock. At first, this lean was subtle, unnoticed by the jubilant crowd, yet keenly observed by the port captain and onlookers ashore. By 7:23 AM, the tilt worsened. Water began flooding the open walkways, rushing into the engine room, forcing crew members to scramble for safety. Just five minutes later, at 7:28 AM, the Eastland tipped sharply at a 45-degree angle. A piano on the promenade deck crashed against the port wall, nearly crushing two women, while a refrigerator pinned others beneath its weight. Water poured into cabins through open portholes.

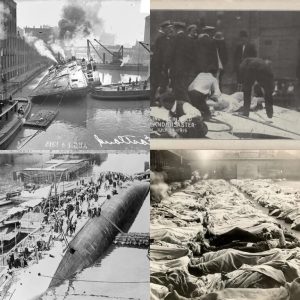

In two devastating minutes, the Eastland flipped over into six feet of murky river water, still docked to the pier. The deadliest shipwreck in the Great Lakes history had begun.

A Defective Vessel and a Fatal Oversight

The Eastland was a disaster waiting to happen. Built in 1902 to carry 500 passengers and transport agricultural goods, it was designed without a keel, relying instead on poorly planned ballast tanks for stability. Its shallow draft and top-heavy structure made it notoriously unstable, earning it the ominous nickname of hoodoo boat among cautious passengers. Modifications over the years may have increased its speed and capacity, but they further jeopardized its stability. In 1904, it nearly capsized with 3,000 people aboard; in 1906, it had a severe list with 2,530 passengers. Yet, safety inspectors, focused solely on the vessel’s navigation performance, routinely certified it as safe.

The tragedy of the Titanic in 1912 prompted global calls for enhanced maritime safety. In the United States, the LaFollette Seamens Act of 1915 mandated that lifeboats be available for 75% of a ship’s passengers. Complying with this law, the Eastland carried 11 lifeboats and 37 life rafts, as well as enough life jackets for everyonemost stored above deck. However, this added weight, approximately 500 kg per raft and 2.7 kg per life jacket, had never been tested for its effect on the ship’s stability. A manager from the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company had warned Congress that such weight could cause shallow-draft Great Lakes vessels to capsize, but his caution went unheeded.

The metacentric height of the Eastlanda measure of a ship’s ability to right itself after being tiltedwas just ten centimeters, far below the recommended range of sixty to one hundred and twenty centimeters for ships carrying variable passenger loads. As historian George W. Hilton noted in “Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic,” the ship behaved like a bicycle, stable only when in motion. On that fateful morning, docked and overloaded, it was an impending disaster.

Chaos and Courage on the Chicago River

As the Eastland continued to list, chaos descended onto the decks. Passengers on the upper decks were thrown into the river like ants flung from a tabletop, as a reporter from the Chicago Herald, Harlan Babcock, vividly recalled. The water turned dark with people struggling and crying out for help. Babies floated like corks; parents clutched their children only to lose them to the currents. The screams were horrific, still echoing in my ears, remembered an employee from the warehouse. Some passengers, like Sladkey and Captain Harry Pedersen, jumped overboard to the starboard side and made their way safely across the exposed hull with nearly dry feet. Others were not as fortunate.

The riverfront, crowded with 10,000 merchants, patrons, and employees from Western Electric waiting for other boats, transformed into a scene of desperate heroism. Spectators leaped into the water, throwing planks, ladders, and wooden crates to aid in the rescue efforts. Some crates struck passengers, rendering them unconscious. One man, who contemplated suicide at the rivers edge, instead dived in to save lives.

Helen Repa, a nurse from Western Electric, heard the desperate shouts from blocks away. Arriving at the scene dressed in her nurse’s uniform, she climbed onto the hull of the Eastland, coordinating rescues while bodies were pulled from the portholes, and survivors were fished out of the water. When a nearby hospital became overwhelmed, Repa arranged for 500 blankets from Marshall Field & Company and hot soup from local restaurants. She instructed passing cars to take the less injured home, noting that no driver ever refused her request.

By 8:00 AM, most survivors had been saved. The grueling task of recovering bodies trapped in the portside cabins began. Divers worked tirelessly to rescue women and children who had sought refuge below deck. The crowding and confusion were terrible, Repa wrote. Seven priests arrived to offer last rites, but as one reporter remarked, the aftermath of the Eastlands capsizing could be summarized in just two words: alive or dead.

A City in Mourning

The death toll from the disaster was staggering: 844 passengers, 70% of whom were under the age of 25, perished in the cold waters of the Chicago River, just six feet from the shore. Entire families were wiped out, including the Sindelar familyGeorge, Josephine, and their five children ranging from ages three to fifteen. The Novotny familyJames, Agnes, and their two children, Mamie and Williemet the same fate. Caroline Homolka and Anna Quinn, the young women who had dressed with such care for the outing, never returned home. Their sisters, Blanche and Alice, waited in vain at a streetcar station, watching covered survivors return muddy and hurt.

The Arsenal of the Second Regiment turned into an impromptu morgue, with bodies laid out in rows of 85. Families lined up to identify their loved ones, joined by curious onlookers and thieves who looted jewelry from the deceased. By July 29, all but one body had been recovereda boy dubbed Little Buddy by the police. The gift from his grandmother, a pair of brown trousers, confirmed that it was Willie Novotny, age seven, whose entire family had vanished. His funeral, alongside his parents and sister, attracted over 5,000 mourners, with a procession that stretched more than a mile and a half.

The Polish, Czech, and Hungarian communities of Chicago, close to the Hawthorne Works, were devastated. Countless homes were draped in black crepe, and the citys cemeteries struggled to keep up with the volume of burials. By July 28, nearly 700 victims had been laid to rest, with 150 graves dug solely in the Bohemian National Cemetery. Marshall Field & Company provided trucks to address the shortage of hearses while 52 gravediggers worked grueling twelve-hour shifts.

A Tragedy Buried by Time

The disaster of the Eastland took more passengers’ lives than the Titanic (829) or the Lusitania (785), yet it faded from collective memory. Why? There were no wealthy or famous individuals aboard, explained Ted Wachholz from the Eastland Disaster Historical Society. Those who suffered were all immigrant families of modest means. Unlike high-profile transatlantic liners, the victims of the Eastland were everyday workers, and their tragedy unfolded not at sea but on a slow-moving urban river.

Blame was quickly assigned. Captain Pedersen and Chief Engineer Joseph Erickson were detained, partly for their own safety, away from an enraged crowd. Seven inquiries were launched within days, with Cook County officials accusing the U.S. Steamboat Inspection Service. Federal lawsuits, overseen by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, dragged on for 24 years. Erickson, used as a scapegoat due to the mishandling of ballast tanks, died during the process, sparing him from deeper scrutiny. Pedersen and the steamship company officials faced no criminal charges, and civil lawsuits yielded little for the victims’ families due to maritime law limiting liability to just $46,000 for the Eastland, much of which went to salvage and coal companies.

The true culprit, Hilton argued, was the ship itselfa poorly designed vessel that had been burdened by safety measures implemented after the Titanic that were never adequately tested. The legacy of the Eastland serves as a poignant reminder of the costs of unchecked regulation and corporate negligence, an unspeakable tragedy that claimed 844 lives in mere minutes, yet has been quietly buried by history.

Leave a Reply